Creating a sufi soundscape: recitation (dhikr) and spiritual audition (samā‘) according to ahmad kāsānī dahbidī (d. 1542)

Alexandre Papas

Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, Paris

Introduction

In both Central Asia and China, as in other Muslim societies, discussions and debates on recitation (dhikr) and spiritual audition (samā‘) were and still are widespread. If we look for the origins of these Sufi techniques in Xinjiang, it seems that in the case of the Naqshbandiyya, the debate was rather different from that of modern times (Lipman 1997). Concerning recitation, the dispute did not oppose silent to loud recitation, khufī and jahrī; and regarding spiritual audition, the discussion was not related to its legitimacy within the Naqshbandiyya. Actually, this question did not arise before the late 18th century. To reconsider the original practice and theory of dhikr and samā’, I will summarise two unpublished writings (in Persian) of one of the most influential Sufi thinkers for Eastern Turkestan, namely Ahmad Kāsānī Dahbidī, a 16th-century Naqshbandi master who lived in Samarkand (Papas 2008), but whose descendants known as Khoja Makhdūmzāda spread all over the Tarim Basin. I use a manuscript copied in 997-8/1589-90, so quite early after the author’s death.

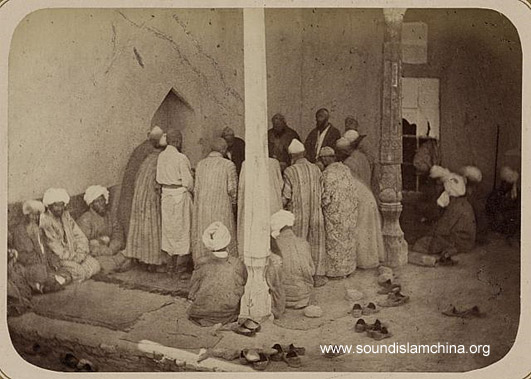

Loud recitation (dhikr-i jahrī), Turkestan, 1860-70s (Turkestanskii Al’bom. Part 2, vol. 1, pl. 65, no. 183)

Treatise on dhikr

Ahmad Kāsānī begins by arguing that “the superiority (afzaliyyat) of our dhikr over other dhikrs is that the expression “there is no other than god” (lā ilāha ilallāh) is of two parts”. In the first part, there is the negation of the otherness, in the second part there is the confirmation of God in heart. For the Naqshbandis, excellent above all recitation (adhkār) is the dhikr of lā ilāha ilallāh since, following the negation of the other from heart, the practitioners find the confirmation of God’s presence in their heart. In other words, after removing from heart the “lā ilāha” which marks the otherness (ghayriyyat), they establish in heart the “ilallāh”, that is to say, the love of God. Thus, once the negation of otherness and confirmation of the beloved are accomplished, any sign of the life is banished from the Sufi’s heart so that nothing remains but the love of God. Then, paradoxically, the Sufi is no longer conscious but is not without attention (khuzūr u āgāhī).

Now, we read, the Sufi practitioners are of three kinds i.e. the beginner (mubtadī), the intermediate (mutawassit) and the accomplished (muntahī).

The dhikr of the beginner is as follows: the Sufi must say (guft) lā ilāha ilallāh within three movements (harakāt) and three pauses (wuqūf), he must practice retention of the breath under the navel, the tongue stuck to the palate, the breath should be considered his last breath, a voluntary suffocation. Several conditions are to be met for the dhikr performance: one is to speak from the heart to the heart, not from the stomach, which does not give results. Speaking “from the heart” means speaking with the thought that resides in the true heart. Speaking “to the heart” means speaking to the body part in the form of a pine cone located in the left side. Another condition is that the movements of the body do not appear in front of yourself but are abstract (ma’nawī). There is some ambiguity here, between loud and silent techniques: Kāsānī does not reject explicitly loud recitation but certainly favors silent recitation as a more advanced and more sophisticated practice.

The dhikr of the intermediate is as follows: It is performed by the metaphoric heart (dil-i majāzī) which resides in the body part forming a pine cone but without the aforementioned difficulties. At this time, all troubles have disappeared and the heart reaches the wuqūf-i qalbī, this until the Sufi stops talking (az guftan bāz īstad). This suggests that dhikr is becoming silent. For some practitioners, they can be so unconscious that they become permanently unconscious. This is the stage of fanā-yi fanā where the Sufi’s existence is annihilated and no trace of being remains.

The dhikr of the accomplished is as follows: it is the stage of fanā-yi fanā where attention to God is the essence, when there is no longer consciousness and nothing of the humane characteristics remains, but when God replaces the being. It corresponds to the fanā-yi fanā-yi fanā, the perfect annihilation. At this moment, the Sufi is equally present to himself and present to God.

Clearly, the point here is not so much the choice between sound and silence but the choice of the appropriate technique for a particular Sufi adept within the same community. According to his abilities and along his spiritual progress, the Sufi may use different types of recitation, reflecting variety but also hierarchy in Sufi circles.

Silent recitation (dhikr-i khufī), Turkestan, 1860-70s (Turkestanskii Al’bom. Part 2, vol. 1, pl. 65, no. 184)

Treatise on samā

Ahmad Kāsānī explains that the reason for writing this text is that the current ‘ulamā who are not members of the Naqshbandiyya, who never met this group and never shared a suhbat (conversation) with them, are opposed to the Naqshbandis and their spiritual practices.

Among all the advantages of samā’, we read, one is that companions practicing Sufism are sometimes so preoccupied with the multitude of activities that they get tired (kalāl wa malāl) in body and mind. Recent masters, because of the problems caused by this kind of accidents encouraged listening to sweet voices, harmonious lyrics and exciting poetry since they can inflame mystical desire and remove lassitude. The second advantage is for the disciples who are stuck in the middle of their spiritual progress. Listening to sweet voices, harmonious lyrics and exciting poetry can produce the hidden qualities that put mystical love in motion. In an instant, the disciple mounts several steps in spiritual progress which, without samā’, could not be crossed in several years.

The problem, according to Kāsānī, is that these advantages have been misunderstood and progressively deviated from their proper purpose. However, the Naqshbandis are aware that, in a time of darkness, it is not possible to reject a practice such as samā’ since listening to fine voices is listening to the sounds of Truth (mukhātabāt-i haqq). Another problem is that man is composed of spirituality (rūhāniyat) and sensuality (nafsāniyat). Everyone who is victorious in one of these two tendencies follows this one. If spirituality is predominant, someone who listens to fine voices will be brought to God. On the contrary, the careless ones (ghāfilān) are oriented towards negligence, and fine sounds make no impression on them. Lastly, when sensuality is preeminent, if someone listens to fine voices, he is inclined towards fornication (zinā’) and obscenity (fisq). In other words, the practice of samā’ itself is neither the cause nor the problem; the real stake is the nature of the individuals.

Each person who follows the Sufi path uses a particular knowledge (bi ‘ilmī-yi makhsūs): the science of dhikr-i jahr or dhikr-i khufiyya, or tawajjuh (concentration), or murāqaba (contemplation), or jadhba (ecstasy), or rābita (paranormal connection between master and disciples), or samā’ i.e. listening to fine sounds (shinīdan-i alhān-i tībat), or eventually suhbat (conversation between master and disciples).

Conclusion

Like dhikr, spiritual audition appears as a popular technique among the Naqshbandis but, unlike dhikr, it was rejected by a part of the religious elite in 16th century Central Asia. During the 17th and early 18th centuries, as I have shown elsewhere (Papas 2004), the Khoja Makhdūmzāda of Eastern Turkestan promoted samā’ as well as dance (raqs) despite their controversial status. Ahmad Kāsānī and his descendants maintained distinctions and hierarchies between Sufi sound practices but admitted all of them, provided that this varied production of ritual sounds (recitation, singing, music, screams, lamenting, etc.), which correspond to the various profiles and advancements of disciples, was under the strict control of the master. I would suggest that this flexibility, theorized by one the main Sufi authorities of Central Asia, contributed to the creation of the long-standing plurivocal Sufi soundscape of Xinjiang, including perhaps its contradictions and conflicts throughout the modern period.

REFERENCES

Kāsānī Dahbidī, Ahmad. Majmū‘a-yi rasā’īl. Ms. FY 649. Istanbul: İstanbul Üniversitesi Kütüphanesi.

Lipman, Jonathan N. 1997. Familiar Strangers. A History of Muslims in Northwest China. Seattle and London: University of Washington Press.

Papas, Alexandre. 2004. Dansez et chantez” : le droit au samā‘ selon Āfāq Khwāja, maītre naqshbandī du Turkestan (XVIIe siècle). Journal d’histoire du soufisme. 4. 189‑200.

Papas, Alexandre. 2008. No Sufism without Sufi orders: Rethinking Tarîqa and Adab with Ahmad Kâsânî Dahbidî (1461 1542). Kyoto Bulletin of Islamic Area Studies. 2/1. 4 22.

All rights reserved © Sounding Islam China (SiC) 2013.

All rights reserved © Sounding Islam China (SiC) 2013.